What Campaign Contributions Tell Us About Congressman Alex Mooney

The Federal Election Commission recently published the 2018 First Quarter campaign contribution filings by candidates for federal office. Among these was the filing of our own Congressman Alex Mooney. Mooney has been very successful in raising money, both for the primary just past (he was unopposed) and for the general election coming up in November. Running for Congress is expensive and anyone who hopes to be elected must raise money. But the sources of Mooney’s contributions for this election cycle raise substantial doubt that he will be much interested in the welfare of West Virginia and her citizens.

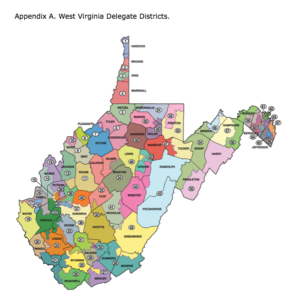

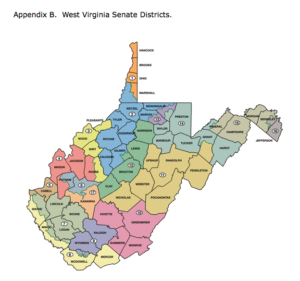

Congressman Mooney is one of the more conservative members of the House of Representatives. He is a member of the “Freedom Caucus” led by Mark Meadows (R-N.C.), which regularly confounds even moderate Republicans by blocking spending initiatives. By now the story of Mooney’s arrival in West Virginia has been told many times. Mooney served in the Maryland Senate from January 1999 to January 2011, where he represented a district that included Frederick. In 2010, Mooney was elected Chairman of the Maryland Republican Party, where he served as Chairman until early 2013. In that year he moved to Charles Town, West Virginia and began his run for Congress, to which he was elected for the first time in 2014. He filled the 2nd District seat vacated by Shelley Moore Capito.

Don’t take my word for Congressman Mooney’s hostility to progressive policy. The website VoteSmart compiled ratings by various political interest groups for 2017-2018. Here are a few: Congressman Mooney was rated 0% by the Planned Parenthood Action Fund, 0% by the Humane Society’s Legislative Fund, 0% on the NAACP Civil Rights Report Card, 0% on the National Education Association Report Card, and 0% on the League of Conservation Voters National Environmental Scorecard.

Congressman Mooney’s contributors tell us a lot about whose interests he will have in mind as an elected official, and who will have access to him. As mentioned, statistics for the state of residence of individual contributors and for the amount of those contributions are available for the full election cycle to date. His individual contributors are overwhelmingly not West Virginia residents.

For this election cycle so far, Congressman Mooney has raised a total of $527,582 from out-of-state contributors, 87.4% of his total individual contributions. By contrast, his opponent Talley Sergent has raised a total $107,815 from out-of-state contributors, 55.2% of her individual contributors. Two things are clear from this. Congressman Mooney has raised much more money so far than Sergent and much more of his money comes from out-of-state contributors.

Think about this for a moment. Why would individual contributors from California or Colorado contribute so much cash to a candidate for the 2nd District Congressional race in West Virginia? I’m willing to bet it is not because of their concern for the citizens of West Virginia. Most of these contributors probably couldn’t find West Virginia on a map.

Most likely they contribute to Congressman Mooney because of his overall conservative credentials. Perhaps he appeared on some list of ideologically pure Republican candidates. They want Mooney to win because they think he will satisfy their interests. So if Congressman Mooney were a calculating man, he might occasionally be inclined to support ideologically conservative positions satisfactory to this contributor base, even when these positions conflict with what is best for West Virginia.

In several cases this appears to be exactly what Congressman Mooney has done. He was relentless in his efforts to repeal Obamacare, red meat for conservatives. In this process he voted for the American Health Care Act that would have rendered 175,000 West Virginians without health insurance.

In the environmental arena, Congressman Mooney celebrated President Trump’s roll-back of the Obama administration’s Stream Protection Rule, which was designed to blunt the harmful effects of mountaintop removal mining. The science on this is not in doubt — mountaintop removal poisons streams, kills fish and wildlife and pollutes drinking water. A ruined environment, fueled by Big Coal and conservative science-denial, directly harms our means of achieving prosperity and our enjoyment of life. But Congressman Mooney is camped out on the wrong side of this issue.

But perhaps the greater cause for worry is the source of Congressman Mooney’s other contributions — corporate PACs. In-house corporate PACs select candidates to support who will be most likely to vote in line with the corporation’s interests. They aren’t just giving away money for the good of the political process. And once elected if the candidate does not reliably vote on these issues, the contributions dry up. Corporate PACs that have contributed to Congressman Mooney will expect their lobbyists to have easy access to him, and that his is a vote they can count on.

So which corporations and industry groups think Congressman Mooney will be a reliable vote on issues that concern them? Here is a selection of many: The American Bankers Association, AT&T PAC, Duke Energy Corp. PAC, Chesapeake PAC, Coal PAC, KOCHPAC, Marathon Petroleum Corp. Employees PAC, NRA Political Victory Fund, and the Goldman Sachs Group PAC. Since these energy and financial PACs clearly think they have something to gain by contributing to Congressman Mooney, then I think they do as well. That is the problem.

Money in politics is a problem for both parties after the Citizens United decision, and Congressman Mooney is not the only politician who accepts corporate PAC money. But Sergent has come out in support of overturning Citizens United and is cooperating with the group End Citizens United. She has received a lone $1,000 campaign contribution from a friend out of his law firm’s PAC, but other than that she has received PAC money only from non-corporate, member-based PACs that have been approved by End Citizens United. These have come from groups such as The West Virginia Education Association and the Women Under Forty PAC.

Until we change our system for funding political campaigns we will have to live with the taint and skepticism that big money contributions create. The real risk, of course, is that these contributions will create more than just a public skepticism of the political process but instead actual pay-for-play corruption. It is my speculation that the lobbyists from the corporate PACs mentioned above have Congressman Mooney’s office on their speed-dial. Is it corrupt when a corporate lobbyist has better access than others to a Congressmen because of heavy contributions from a corporate PAC? I find it hard to escape this conclusion.