Partisan Gerrymandering and the Constitution

On October 3, 2017, the United States Supreme Court will hear arguments in the case of Gill v. Whitford. This case raises the question of whether gross partisan gerrymandering by the Wisconsin state legislature in creating state voting districts violates any provision of the U.S. Constitution. Partisan gerrymandering – intentionally drawing voting district lines to favor one party or the other – has seen a sharp increase since the redistricting that followed the 2010 census. Many observers believe that partisan gerrymandering is to blame for much of the gridlock in Congress and the state legislatures because highly partisan districts elect highly partisan representatives who have no political room to compromise. The old legal wisdom is that for every wrong there is a remedy, so you would expect that this case would be a slam-dunk for those challenging the Wisconsin redistricting in the Supreme Court. But you would be wrong.

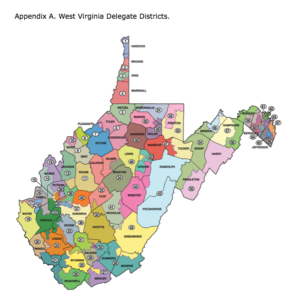

First, some basics. The constitutions of each state determine the number of state Senators and Delegates assigned to voting districts and the apportionment of the state’s population into those districts. In West Virginia the House of Delegates is composed of a fixed 100 members, each theoretically representing 1/100 of the state’s population. But instead of there being 100 districts, our legislature has created 67 districts some of which elect multiple Delegates. (Appendix A). All Delegates face re-election every two years.

First, some basics. The constitutions of each state determine the number of state Senators and Delegates assigned to voting districts and the apportionment of the state’s population into those districts. In West Virginia the House of Delegates is composed of a fixed 100 members, each theoretically representing 1/100 of the state’s population. But instead of there being 100 districts, our legislature has created 67 districts some of which elect multiple Delegates. (Appendix A). All Delegates face re-election every two years.

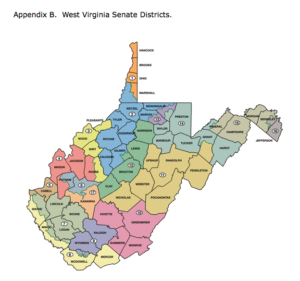

There are two Senators from each of seventeen senatorial districts for a total of thirty four. According to the West Virginia Constitution, senatorial districts “shall be compact, formed of contiguous territory, bounded by county lines, and, as nearly as possible, equal in population, to be ascertained by the census of the United States.” (Appendix B). There is no such language relating to House districts. Senate terms are four years and elections are staggered so that a portion of senators faces re-election every two years.

State legislatures also draw each state’s Congressional district boundaries, which must be revisited every ten years immediately after the census. West Virginia has had three Congressional districts for several decades, but their boundaries have changed slightly over time to reflect the shift in population to the Eastern Panhandle and Monongalia County. The U.S. Constitution and its Amendments determine who can vote in federal elections. But as for how districts are constituted, it merely says that “Representatives . . . shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective numbers” and that “the number of Representatives shall not exceed one for every thirty Thousand.”

State legislatures also draw each state’s Congressional district boundaries, which must be revisited every ten years immediately after the census. West Virginia has had three Congressional districts for several decades, but their boundaries have changed slightly over time to reflect the shift in population to the Eastern Panhandle and Monongalia County. The U.S. Constitution and its Amendments determine who can vote in federal elections. But as for how districts are constituted, it merely says that “Representatives . . . shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective numbers” and that “the number of Representatives shall not exceed one for every thirty Thousand.”

The basic requirement of Congressional apportionment that each district have an approximately equal population is consistent with the 5th Amendment’s promise of equal protection of the law. For example, if District A has a population of 750,000 and District B has a population of 800,000, then voters in B have an incrementally less powerful vote. That same principle was made applicable to the states by the 14th Amendment, ratified after the Civil War. In a series of cases in the 1960s, the Supreme Court announced that “equal protection” in the context of state legislative district apportionment meant “one person, one vote.” For example, in Reynolds v. Sims (1964), the Court said:

To the extent that a citizen’s right to vote is debased, he is that much less a citizen. The fact that an individual lives here or there is not a legitimate reason for overweighting or diluting the efficacy of his vote. . . . By holding that as a federal constitutional requisite both houses of a state legislature must be apportioned on a population basis, we mean that the Equal Protection Clause requires that a State make an honest and good faith effort to construct districts, in both houses of its legislature, as nearly of equal population as is practicable.

But if all equal protection requires is districts of equal population, there is still an infinite number of ways to divide a state’s population into roughly equal segments. The development of software that predicts the likely election consequences of moving even small groups of voters from one district to another has tempted legislatures to find just those configurations that maximize the likely future success of the party in power, while still satisfying the equal population requirement. The Republican legislators in Wisconsin sorted through multiple proposed district maps with the use of redistricting software and the help of political science experts until they found the one they believed would best ensure their control of the legislature for an entire decade even if they were to lose the popular state-wide vote.

The challengers to this plan in Wisconsin were numerous individuals and groups acting on behalf of Democrat voters in the state. There is a subtle but significant difference between protecting an individual voter from the dilution of her vote and protecting a subset of the whole voting population – registered Democrats – from being deprived of a proportionately equal chance to elect Democrat candidates. This difference raises the question of whether the Equal Protection Clause even applies to state-wide voter groups? If it does, are all such groups entitled to equal protection? If Democrats and Republicans as distinct voter groups are entitled to equal protection, how about the Green Party or the American Nazi Party? This is one thing that makes the issues raised in the Wisconsin case so difficult for courts to get their minds around.

There is even a more fundamental legal question the Court must answer before deciding whether the Equal Protection Clause prevents partisan gerrymandering. That question is “justiciability” – whether a clear rule can be found delineating what is acceptable from unacceptable in the drawing of district boundaries and whether courts should step into the political arena at all in view of the separation of powers. In my next post, I will explain why partisan gerrymandering greatly intensified after the Supreme Court’s last pronouncement on these issues in 2010, and where the law now stands on the issues presented in the Wisconsin case.